Nestled in the rugged Sierra Nevada, Carson Valley was certainly appealing for pioneers fortunate enough to pass through on their way to California. With open space, plenty of water, and the resources to develop the land and raise cattle, the valley was the perfect place to set up camp.

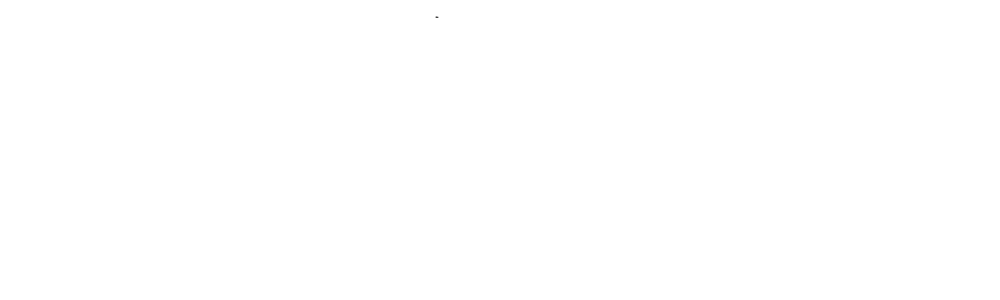

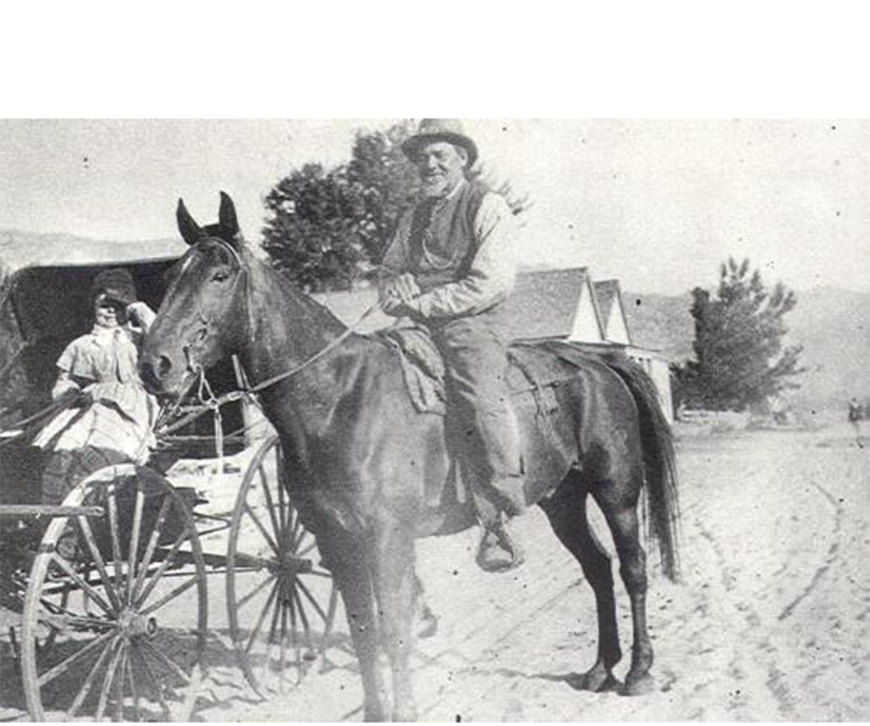

Ben Palmer (or was it Parmer?) came into the valley’s history with a veil of mystery draped over his early life. His birthday, birthplace, and early life are still disputed, including the spelling of his last name. A local Historian, Grace Dangberg, has suggested Ben and his sister, Charlotte, may have been Missouri slaves who purchased their freedom. While his exact origin is uncertain, we do know Ben claimed 320 acres of grassland just south of Genoa in 1853. We also know Charlotte married a white settler, David Barber, and settled 400 acres on a plot of land next to Palmer’s.

Known as a skilled cattleman and driver, Palmer introduced the rare Bonner breed of horse into the area. He went on to physically shape the valley by building dams and ditches to irrigate the fertile grazing lands that he rented to passing emigrants from late spring to early fall. By 1857, Palmer’s herd was shrinking from his ever-expanding business. That same year he drove 1,500 head of cattle over 700 miles from Seattle to Carson Valley, helping to improve the bloodlines of the valley’s cattle. The next year a local newspaper reported he drove 450 head of cattle through Genoa on his way to Goose Lake, Oregon.

Palmer’s hard work paid off. In 1857, his assessed value was more than $5,000, a very considerable amount in those days. By 1867, Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise listed Parmer as one of the heaviest taxpayers in Douglas County. His total worth was later valued to be over $17,000.

Palmer became a prominent member of the community in a period of time that gave few advantages to black men. The Nevada Territorial Legislature had laws barring African Americans from voting, holding office, serving on juries, and testifying against whites. Schools were restricted to white children and interracial marriages were outlawed. Even after Nevada entered the Union in 1864, things largely remained the same, black children were still constitutionally excluded from attending white public schools.

Palmer was ahead of his time, hiring Native-American, black, and white farmhands. His white neighbors respected him so much, they invited him to register and vote in the Mottsville Precinct. The invitation came before the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment which gave African American men the right to vote. Ben threw his hat into the political arena in 1878 as a member of the Douglas County Central Committee and became a registered voter in 1879. He voted regularly the rest of his life. Ben further served on the county grand jury and was appointed to the panel of trial jurors for that year’s term of district court.

Ben didn’t let success slow him down, or so the story goes. In 1891, around the age of 60, Ben was thrown from his buggy when the front wheel broke off. The tale would end there for most people, but not Palmer. With his team of horses startled and fleeing in fear, Ben held onto the reins while being dragged all around the dirt and sagebrush. He was able to eventually bring the horses under control, sustaining only minor bruising in the process.

Mr. Palmer passed away in 1908, at the age of 82. At that time, the Record-Courier noted Palmer “met success in every meaning of the word and leaves one of the finest farms in Carson Valley as a monument. He bore a man’s part in the battle of life, bore it bravely, gently, and without ostentation”. Palmer was buried in the Mottsville Cemetery, just south of Genoa. A classic red barn is all that remains of the Palmer Ranch, but not Palmer’s legacy.