Carson Valley locals know that a long-ago water wheel on the Carson River was the inspiration behind this fair and carnival mainstay. Special thanks to Cynthia Ferris-Bennet, Mr. Gale’s great-great-grand-niece, for allowing us to excerpt this story from her family genealogy typed in 1935: Memoir and Genealogy of Silvanus Ferris (1773-1861).

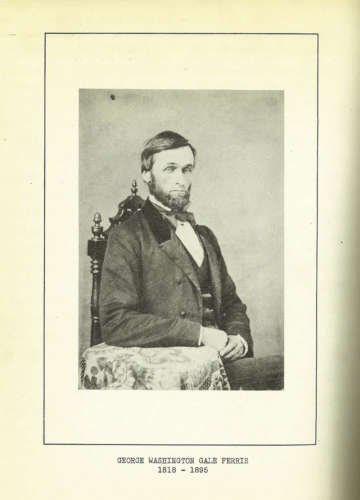

Inventor’s Father.

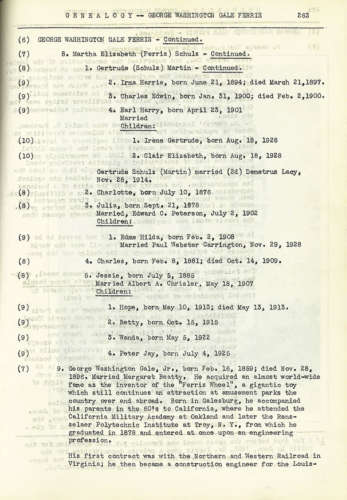

George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr., born Feb. 16, 1859; died Nov. 28, 1896. Married Margaret Beatty. He acquired an almost world-wide fame as the inventor of the “Ferris Wheel”, a gigantic toy which still continues to [be] an attraction at amusement parks the country over and abroad. Born in Galesburg, he accompanied his parents in the 60’s to California, where he attended the California Military Academy at Oakland and later the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute at Troy, N.Y., from which he graduated in 1878 and entered at once upon an engineering profession.

His first contract was with the Northern and Western Railroad in Virginia; he then became a construction engineer for the Louisville Bridge Co., and supervised the construction of the Louisville and Nashville bridge over the Ohio River at Henderson, Ky. In 1882 he organized the engineering and bridge designing firm of G.W.G. Ferris & Co. at Pittsburgh, Pa., which was thereafter his home, and this firm, which continued in existence until shortly before his death, built the cantilever bridge over the Ohio at Cincinnati, an outstanding engineering achievement at the time.

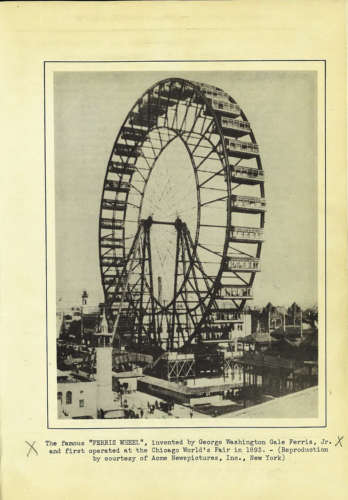

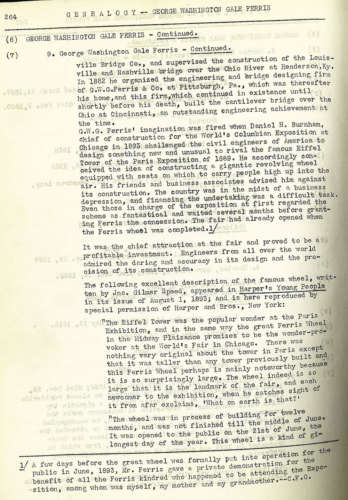

G.W.G. Ferris’ imagination was fired when Daniel H. Burnham, chief of construction for the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893, challenged the civil engineers of America to design something new and unusual to rival the famous Eiffel Tower of the Paris Exposition of 1889. He accordingly conceived the idea of constructing a gigantic revolving wheel equipped with seats on which to carry people high up into the air. His friends and business associates advised him against its construction. The country was in the midst of a business depression, and financing the undertaking was a difficult task. Even those in charge of the exposition at first regarded the scheme as fantastical and waited several months before granting Ferris the concession. The fair had already opened when the Ferris Wheel was completed.

It was the chief attraction at the fair and proved to be a profitable investment. Engineers from all over the world admired the daring and accuracy in its design and precision of its construction.

The following excellent description of the famous wheel, written by Jno. Gilmer Speed, appeared in Harper’s Young People in its issue of August 1, 1893; and is here reproduced by special permission of Harper and Bros., New York:

“The Eiffel Tower was the popular wonder at the Paris Exhibition, and in the same way the great Ferris Wheel in the Midway Plaisance promises to be the wonder-provoker at the World’s Fair in Chicago. There was nothing very original about the tower in Paris except that it was taller than any tower previously built and this Ferris Wheel perhaps is mainly noteworthy because it is so surprisingly large. The wheel indeed is so large that it is the landmark of the fair, and each newcomer to the exhibition, when he catches sight of it from afar exclaims, ‘What on earth is that?’

“The wheel was in process of building for twelve months, and was not finished till the middle of June. It was opened to the public on the 21st of June, the longest day of the year. This wheel is a kind of merry-go-round, swinging vertically instead of horizontally. The wheel is 250 feet in diameter, 825 feet in circumference, and 30 feet in width. As it is elevated fifteen feet above the ground, the passenger at the top gets a view at an elevation of 265 feet. It is composed of two wheels of the same size connected and held together with rods and struts, which, however, do not approach closer than twenty feet to the periphery or outdoor surface. Each wheel has for its outline a curved, hollow, square iron beam 25 1/2 x 19 inches. At a distance of forty feet within this circle is another circle of a lighter beam. These beams are called crowns, and are connected together by an elaborate truss-work.

“The wheel has thirty-six cars for passengers hung on its periphery at equal intervals. Each car is 27 feet long, 13 feet wide, and 9 feet high. It has a heavy frame of iron, but is covered externally with wood. It has a door and five broad plate-glass windows on each side. It has forty revolving chairs made of wire and screwed to the floor. It weighs thirteen tons and when loaded with passengers three tons more. Each car is suspended to the periphery of the wheel by an iron axle six and one-half inches in diameter and running through the roof. There is a conductor to each car to open doors and give information.

“To prevent accidents from panics, and also to deter insane persons from jumping out, the windows are covered with iron gratings. As the wheel, with its cars and passengers, weighs about 1200 tons, it needs something substantial to rest upon. Its axis is therefore supported on two skeleton iron towers, pyramidal in form, one at each end of it. They are 40 x 50 feet at the bottom, 6 feet square at the top, and about 140 feet high. Each tower has four great feet, and each foot rests in a concrete foundation 20 x 20 x 20 feet, all of these foundation piers being bound together by connecting rods of steel.

“The wheel is moved and controlled by a 1000-horsepower steam-engine, while the periphery is cogged with cogs 6 inches deep and 18 inches apart. Underneath the wheel in line with the crown on each side, are two sprocket-wheels 9 feet in diameter, with their centres 16 feet apart. These sprocket-wheels are operated by the engine at the will of the engineer, who can turn the wheel either way, fast or slow, as he may wish. Near the north and south ends are two ten-foot wheels, with smooth faces, and girdled with steel bands. These bands terminate a little to one side in a large Westinghouse air-brake. If, therefore, anything should break, or the engine refuse to work, the air could be turned into the air-brake, and the steel band tightened until not a wheel in the whole machine could turn.

“On the opening day the Iowa State band was in the first car, and played the Star Spangled Banner and Dixie as the wheel revolved with its first load of passengers. The cars moved up so slowly that their motion was almost imperceptible and quite noiseless. It seemed as if the earth were sinking away out of sight slowly and quietly – and it sunk to an astonishing distance too. Going up the passengers had the whole of Chicago and Prairies for miles beyond laid before them unobscured. Going down there was a clear view of the World’s Fair — the White City being seen at a single glance, while the sail-dotted lake was beyond, and the swarming Midway Plaisance right beneath. It is when the car gets right at the top of the wheel, and the passenger pokes his head out and looks down to see how far away and how insignificant is the big axle in the centre of the tangle of steel rods, that he best realizes how tall the Ferris Wheel is, and how far the passenger is from the firm earth.

“The sensation made by a ride on the wheel were different in each passenger. Some of them were undoubtedly frightened, just as a timid countryman is frightened when first riding in one of the quick moving elevator cars of a tall building; but the fright was a pleasurable one, even if it did for the moment take the breath away. The poets and fine writers are already beginning to get in their work on this great engineering achievement. Mr. Eugene Field, the Chicago poet, in singing the delights of the Midway Plaisance, has said

‘The Ferris Wheel, with arms of steel,

High as a tower will wind you up;

If you should fall, for good and all,

The doctors they would bind you up.’”

After the fair closed, the when and reproductions of it were set up as attractions at amusement parks all over the country and even abroad; imitations of it are still commonly to be seen. But the enterprise ceased to be remunerative to its inventor, whose later days were saddened by seeing this spectacular child of his brain seized by a sheriff, and indeed this event is said to have hastened his death, which occurred at Pittsburgh, Nov. 28, 1896. He left no children.

“A few days before the great wheel was formally put into operation for the public in June, 1893, Mr. Ferris gave a private demonstration for the benefit of all the Ferris kindred who happened to be attending the Exposition, among whom was myself, my mother and my grandfather.” Charles Ferris Gettemy

Learn more about exploring Carson Valley, where the inspiration for the Ferris Wheel was found, and make your own legendary memories.